- Home

- Jean La Fontaine

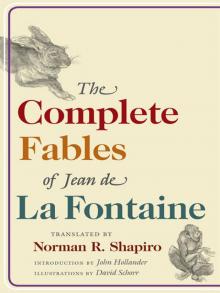

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Page 12

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Read online

Page 12

I do so, rather, only to portray

Our customs. For, myself, I am above

Such base ambition; though, speaking thereof,

I must admit that Phaedrus,2 in his day,

Sought not a little glory. Anyway,

My fable: of a father who decided

To warn his sons lest they become divided.

An old man, feeling he was soon to be

Called to where he would spend eternity,

Summoned his sons. “Children,” so he addressed

All three, “I bid you come hither and test

Your strength upon these arrows, tightly tied

Into a bundle. When you all have tried

To break them, I shall then explain the knot

That binds them.” One son tried, the eldest, got

Not very far before, with huff and puff,

At length he cried: “I have not strength enough!

Let someone stronger try!” At which, another,

The second, took his stance, but, like his brother,

Failed; whereupon, the youngest tried, but could

No better do: the bundle, tough, withstood.

“Weaklings!” the father shouted. “Watch!” They smile.

No doubt he twits and chaffs them! But, the while,

He separates the arrows, easily

Breaks them, and says: “Now I trust you can see

How valuable is unity, mes fils.

Remain forever joined. Let love and peace

Bind you as one.” Silent he lay, as on

He lingered in his malady… Anon,

Sensing the end, he summons them once more.

“Farewell! I join our fathers. But before

I do, I pray you swear that you will be

Forever bound as brothers…” Weepingly

Each takes his hand; he, theirs; so swears… He dies.

The brothers, after his tearful demise,

Find that he left great wealth, but much beset

It was with many a lawsuit, many a debt.

At first, no problem. But soon—any wonder?—

What blood had joined, interest rent asunder.

And when the time came to adjudicate it,

A myriad problems rose to complicate it:

Errors, and disagreements, and deceit;

A judge whose every judgment was replete

With controversy, cavil, condemnation;

At every turn another contestation,

Another disagreement, till each brother

Promptly lost all he had, and blamed the other.

Now how they wished that they had kept in mind

That arrow-bundle, and the ties that bind.

IV, 18

THE ORACLE AND THE INFIDEL

To seek to fool the gods is folly arrant:

The labyrinthine crannies of Man’s heart—

Disguise them though he try, with cleverest art—

Appear before them, clear, transparent.

In fact, his every deed, his every act,

However darkly done, rises intact

Before their eyes. And so my story:

A rustic infidel, a heathen (yet

One who took stock of heaven, to hedge his bet!)

Went to Apollo’s oratory—

The oracle, that is—and, once inside

The holy precincts, boldly cried:

“Tell me, is what I’m holding in my fist

Dead or alive?” Our demi-atheist

Held, so they say, a sparrow; one that he,

At the god’s answer, could set free

Or smother utterly, thereby

Proving him wrong, whichever his reply.

Seeing his plan, “Come now,” Apollo said.

“Fie on your foolish traps! Alive or dead,

Show us your sparrow!… See? My sight is strong.

And, what is more, beware: My arm is long!”

IV, 19

THE MISER WHO LOST HIS TREASURE

Possessions have no value till we use them.

Misers there are, no doubt, who would dissent.

This tale, I trust, will disabuse them:

What does it profit them to hold, unspent,

Pile upon pile of gold? Diogenes,1

For all his poverty, in death, is quite

As rich; and avarice’s devotees

Are quite as poor, in life, as he. Thereto, we might

Consider one of Aesop’s tales:2 the one

About a miser and his hoard,

Who wants to wait until his life is done

(And off he goes to his reward),

To be reborn before he spends his treasure.

With it, his heart lies buried; such

That, day and night, he knows no other pleasure

Than to go worship it; to touch

The ground; to muse, to dream… Eating or drinking,

Coming or going, one thought ever thinking!

Truly, the gold owns him; not he, the gold.

Now, in the interim,

A certain graveyard digger, seeing him

Pay visits to the spot, untold,

Suspects, digs, finds the treasure… And that’s that!

Our miser, one fine day, comes, sees the hole—

Empty, alas!—gazes thereat,

And heartsick, sighing from his very soul,

Weeps, wails, and groans in grief. A passerby

Asks him: “Why all the hue and cry?”

“Why? It’s my money! It’s been stolen… See?”

“Oh? Where?” “Next to that rock!” “Dear me,

Are we at war? Why keep it way out here?

You should have kept it in your chiffonier.

You could have used it when you chose.”

“‘Used it?’ Good God! Do you suppose

It grows on trees? I never spent a sou.”

“You didn’t?” “No!” “Then I suggest

You needn’t rend your hair and beat your breast,

My friend! Here’s all you have to do:

That hole of yours… Go take some stones and fill it.

Really, it won’t make any difference, will it?

They’ll be worth quite as much to you!”

IV, 20

THE MASTER’S EYE

A stag sought refuge with the race bovine

Inside a barn. The oxen thought,

All things considered, that he ought

Best seek another. “Brothers mine,

I pray you, do a kindly deed

And not betray me! By and by

I’ll show you where to find the tastiest feed!”

His oxen hosts agree, comply

With his request for sanctuary.

Off in a corner, much relieved, and very

Grateful, he hides… The servants come, that night,

With fodder… Come, go… In, out… But despite

The hubbub and the feeding fuss,

Stewart and minions are oblivious

To antlered head (and stag in toto!). Quite

Thankful, the forest denizen waits, bides

His time until the varlets leave, to labor,

Tilling fair Ceres’1 field; decides

Now is the time to go. “But, neighbor,”

Bellows an ox, chewing his cud. “Poor deer!

Till now you’ve had no dealings, none,

With him we call ‘the hundred-eyeballed one!’

Don’t be so brash, so cavalier!

Until he comes, himself, to check the herd,

The barn, and all, you haven’t heard the end,

I fear!” No sooner had that final word

Parted his lips than—heaven forfend!—

In stalks the master; makes his rounds…

“What’s this?” he cries. “Gadzooks and zounds!

Look at this filthy litter!… Change it please!…

Go get more fodder!… What are these

Yokes doing here?… And tell me, wh

y

Must there be spiders everywhere?…” And on

And on he rants and cavils; whereupon,

Darting his glance, his eyes espy

An unknown head. Alas, our stag lies caught.

Mid pikes and spears, tears, pleas go all for naught!

They kill him, salt him… Many a mouth will feast

For many a day upon our beast.

Phaedrus it was who proved the point concisely:

“The master’s eye is best!”2 he put it nicely.

(Myself, I’ll add another’s, con amore:

The lover’s too! But that’s another story!)

IV, 21

THE LARK, HER LITTLE ONES, AND THE FARMER WHO OWNS THE FIELD

“Count not on others!” Thus our antecedents

Wisely advised us to behave.

Common the adage. Here’s how Aesop gave

It credence.

Each year the larks would build their nest

Amid the stalks of grain budding to life;

That season green when, passion-rife,

A teeming Nature—birds, plants, all the rest

Of livingkind—gives way to love: sweet spring.

Beasts all, and all with but one notion:

Monsters beneath the briny ocean,

Tigers of forest climes, larks on the wing…

One of the latter, for some reason

Deaf to the urgings of the season

Until it was, alas, half past,

Decided it was time, at last,

To taste the joys of springtime love, and do

Like earth and Nature, and give birth anew.

Quickly she builds her nest, lays, sits… Anon,

She hatches out her brood; but, spring now gone,

The wheat whereon they nested had already

Ripened before the hatchlings—too unsteady,

Too weak of wing yet to take flight—

Had learned to go in search of food.

Wherefore, with much solicitude,

The mother lark, eager to ease their plight,

Goes foraging; but not before

Proffering words of warning by the score,

Telling them they must keep a well-peeled eye

In case monsieur, who owns the field, comes by:

“He and his son,” she says, “as they

Most surely will.” Then, adding: “Listen well!

For, truly, what he has to say

Can seal our fate.” She leaves, and, truth to tell,

Monsieur appears next moment with said son.

“The wheat is ripe. Go ask our friends, each one,”

Says he, “to bring a sickle and come here

At dawn to help us.” Soon our lark returns,

Finds her brood much alarmed, and learns

Quickly the reason for their fear.

“‘At dawn,’ he said… With all his friends… Tomorrow…”

“Indeed? If that was all he said, no worry!

Come feed on what I’ve found. No hurry!

Surely we have no need to go and borrow

Trouble just yet. Tomorrow, once again,

We’ll listen well and, maybe, worry then.”

Meanwhile they supped, then slept… Next day,

Dawn breaks. And friends? No, none… Off flies

The mother. Comes monsieur: “I say,”

Says he, “my wheat still standing? Ah,” he sighs,

“What worthless friends! What good-for-nothing wretches!

Go fetch my cousins all!” And, in the nest,

Our fledgelings, still more sore distressed:

“Now cousins… Cousins, now he fetches…

Cousins galore he’s sending for!…” Another

“Tut tut” of reassurance from the mother:

“Sleep tight. We have no cause to flee.”

And right she was. Cousins? Not one… The third

Day, when monsieur came eagerly

To view his crop, these were the words they heard:

“What fools we are to count on others! We

Can count on but ourselves, you hear?

Tomorrow we—no neighbors, brothers, kin—

Will come, each with our sickle, and begin

Our labors, best we can.” The lark gave ear.

“Now is the time,” she tells her brood. And they

Flutter, untrumpeted, and fly away.

IV, 22

· BOOK V ·

THE WOODSMAN AND MERCURY

FOR M. L. C. D. B.1

Your taste it is that guides my art; I try

To please your gracious audience thereby.

You would have me a florid style eschew,

Pompous and labored. I would do so too.

Such effort is not pleasing, and a poet,

Lest he mar all he writes, had best forego it.

Not that one must reject a certain charm—

Delicacy of touch—that does no harm

And that you find attractive quite as much

As I. Indeed, it is with such

Traits that I try to do as Aesop tried

Before me, with as few faults, flaws

Withal. If neither pleased nor edified

Is he who reads me, it is not because

I do not try. With pointed phrase—

Since, with Herculean force I cannot flout

Vice in its source—I seek to rout

It out with ridicule. I dare not raise

The hope that I succeed. Sometimes my story

Paints envy and foppish vainglory:

Pivots round which our lives revolve these days.

For instance, take that paltry beast

Who sought to see her girth increased

Until she reached the ox’s size.2

Other times I pair vice with virtue, sense

With folly, showing the experience

Of lamb with wolf in blackguard’s guise,

Of fly and ant, rivals forever; whence

A drama in a hundred acts I write,

Whose setting is the universe. Gods, men,

Beasts play their parts, time and again,

And Jove as well. Here let me cite

Mercury too, who does the latter’s

Errands in all his amatory matters.

But that is not the role he has today.

A woodsman lost his bread and butter—

His axe, that is—and stood in utter

Woe and pathetic disarray.

No other tools to sell had he;

Nothing ’twixt him and penury

Complete. As tears stream from his eyes,

Bathing his face, “My axe,” he cries,

“My poor, dear axe! O Jupiter!

Pray give it back to me, Seigneur,

And I will thank you for the boon!”

Olympus hears his plea, and soon

Sends Mercury… He comes… Replies: “It

Has not been lost. But tell me, should

You see it, would you recognize it?

I saw one hereabout that could

Be yours…” Wherewith he holds one out,

Crafted of gold. “Ah, no! I doubt

That would be mine! It cannot be!”

A second one, of silver made,

Followed the first. The woodsman bade

Mercury keep it: certainly,

In no wise was such an axe his.

At length, a third, of wood… “Ah me!”

He shouted joyously. “That is

The very one!” “And yours shall be

The other two as well, all three,”

Answered the god, “as a reward

For virtue, and good faith restored!”

When word about the precious pair

Went spreading, bruited here and there,

How many are the Jeans and Jacques

In feigned despair, who claim that they

Have likewise lost their trusty axe,

A

nd pray the heavens that it may

Soon be returned! Before the lot,

Poor Jove can scarce decide which one

To listen to; and which one, not.

And so once more he sends his son

To earth. Again to each he shows

An axe of gold. Each would suppose

Himself a dolt not to cry: “Ods

Bodkins! ’Tis mine!…” Ah, but instead

Of giving them the axe, the gods’

Runner thwacks them about the head.

Best to speak true and be content

With what is yours. For, what’s the use

Of lying to grow opulent?

Jupiter is no simple goose!

V, 1

THE EARTHEN POT AND THE IRON POT

Said iron pot to earthen pot:

“Let’s travel, you and I.”

Said earthen pot: “I’d rather not,

My friend, and this is why:

For somebody the likes of me

It’s best to stay home peacefully,

Here by the fire. It doesn’t take

More than a touch to make me break

To bits, a-crumble and a-shatter.

With you it’s quite another matter:

Go where you like; your iron hide

Is tough enough.” The pot replied:

“I understand why you object.

You fail to fancy, I suspect,

That I’ll protect you, come what may.

Indeed, you’ll be my protégé:

Should object hard and unforeseen

Come threaten you, I’ll stand between.”

These promises at length persuade

His fretful friend, who, unafraid,

Accepts his offer. Off they go—

Two pots together, forward ho!—

Waddling along three-footedly;

But as they clip-clop, fancy-free,

The earthen pot, with every stride,

Is jarred and jostled by the one beside.

In but a yard or two, our pot—

With little right to wonder “Why?” or “Wherefore?”—

Lies in a shattered heap.

My advice, therefore:

Keep to your kind. Because, if not,

You too may get the fate he got.

V, 2

THE LITTLE FISH AND THE FISHERMAN

Though every little fish, God willing,

Surely, one day, will bigger grow,

Folly it is to let one go

Until he’s fatter for the killing.

Later you well may try, and not be able,

To land him when he’s fitter for the table.

Angling at river’s edge, a fisherman

Captured a baby carp—so goes the fable—

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine