- Home

- Jean La Fontaine

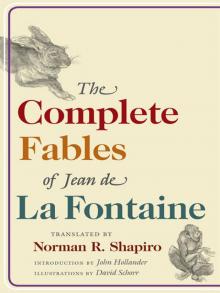

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Page 17

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Read online

Page 17

Waited to find a husband young and fair,

Nor cold, nor jealous; well formed, debonair;

Wealthy and witty, born of high degree:

In a word, perfect. But is there

Anyone so well favored? Destiny

Did all it could to find her one,

Offering many for her contemplation.

Our belle sneered, scoffed them all, found none

Worthy of her consideration.

“They dare woo me? These curs half-baked, half-done?

They must be mad! What twaddle! How I pity

The lot of them!” One was not witty

Enough for her; another’s nose

Was much too sharp; another’s, flat;

Another, this; another, that…

And on and on. For so it goes

With our précieuses, who cast a scornful eye

On everyone. Soon there came by

Wooers of lesser breed, more mediocre,

Who pressed their suit no less therefor, and thus

Succeeded merely to provoke her.

“Ah,” she exclaimed, “how generous

Am I merely to open up my door

And let them in! They must think I deplore,

Abhor my solitude. But no!

I spend my nights alone, and wish it so.”

Pleased was she with such sentiments. But when

Age took its toll, where were the lovers then?

A year goes by… A second… Her dismay

Grows into desperation; now, away

With sport and pleasure; gone her laughter,

And even love itself; soon after,

Gone, too, her beauteous, fetching features—

Disgusting now, despite her hundred potions,

Powders, and paints: no efforts, no devotions

Save her from time, that most thieving of creatures.

The ruins of a house can be

Restored; why can no lotions, creams provide

Help for a face felled by catastrophe!

Our précieuse changed her tune; her mirror cried:

“Go find a husband! Quick! Go find one fast!”

Her passion said so too, unsatisfied—

For passion rules précieuses though youth is past.

No more does she demur or vacillate,

But, happy—who would think?—at last,

To take an ill-formed lout to be her mate.

VII, 4

THE WISHES

Among the Mogols there are genies who

Serve as valets, clean house—dust, sweep—

Tend to the garden, groom the stables, keep

The coach in good repair, and do

Chores of all kinds. But oh! Should you

Lay but a finger on their work, voilà!

You spoil it all. Well, years ago there dwelt

Off by the Ganges’ shore a good bourgeois,

With such a spirit; one who had been dealt

Gardening skills galore, and felt

Most kindly toward monsieur, madame, and worked

Untiring and without complaint, and not

Unaided by those fair southwinds that lurked

About the garden, breezes wafting hot

(Spirit-companions, they!). Yes, gladly would

Our genie have remained, to toil and moil

With his belovèd masters, till the soil

For them forever, if he could.

(And that, despite the most capricious

Nature of genies!) But the brotherhood

Thereof, for reasons—well—suspicious

(Whimsy? Or politics? Or what?

Who knows? I have no notion. But…)

The fact is that they changed this one’s location:

Off to another corner of the map,

Deep in the wastes of Norway’s desolation!

Hindu before, now must he be a Lapp,

And tend a house covered, year-round, with snow!

“Dear friends,” he says, “Before I go—

As go I must, I know not for what sins—

I pray you use the weeks still left to me

To ask me for three wishes. For we jinns,

No doubt you know, can grant Man wishes three—

No less, no more!” Now, wishing, obviously,

Is something Man does well. No need to ask

Them twice. And, warming to the task:

“Pray give us wealth!” Such is their first

Request; and wealth they get, but wealth so vast,

In such abundance, that they stand aghast

Before their larder, crammed, ready to burst;

Their cellars, filled with wine, racks upon racks;

Their coffers, stacked with gold! How many the sacks?

Why, who could count it all? Nor had they any

Manner whereby to keep it safe. For many

The thieves now plotting their attacks;

And many the grands seigneurs who, on the morrow,

Came for their share: beg, steal, or borrow!

(Taxes as well, of course, lest I forget!)

In short, by woe of wealth’s excess beset:

“Misery!” wail our friends. “Please take

Away your treasure and your plenty! Let

The goddess Poverty come make

Us rich once more, mother of sweet content.”

Poverty, at these words returns. Our pair,

At peace again, now with two wishes spent

(Foolishly, but with one yet left), take care

Lest it be wasted on some silly folly.

Smiling a farewell smile, the jolly

Jinn goes to leave. But our two, with an air

Of melancholy, ask: “If it’s your pleasure…

Our final wish!” And with a touch of

Sadness, they ask for wisdom. Ah, a treasure

No one can ever wish to have too much of!1

VII, 52

KING LION’S COURT

His Lion Highness, one fine day, decided

Straightway to learn what peoples heaven above

Had made him sovereign master of,

And to his deputies confided

Forthwith the task of sending for

His vassals: each ambassador

Bearing a royal-sealed decree

Declaring that His Majesty

For one full month was holding court;

That on the opening day a feast

Would welcome one and all; that ape artiste,

Famed Fagotin,1 would then cavort,

Sporting his monkey tricks. And thus

The monarch, with his lavish, generous

Display would prove his power. All would report

Thence, to his Lion-Louvre, his chateau.

But as each one alighted, oh!

What a foul stench of death assailed them there!

Holding his nose, contorted, stood Sire Bear.

Our sovereign leonine was much nonplussed

At such a show of disrespect, and he

Dispatched him most summarily

To Pluto’s realm, to practice his disgust.

The monkey, master of the flattering antic,

Fawning in manner sycophantic,

Finds that the punishment is apt and just;2

Praises the prince, his lair… As for the smell,

No flower, no amber could compare! Ah, well,

Lion condemned him too, for toadying!

(A cousin to Caligula, this king!)

At length, spying the fox: “I say,”

Says he, “tell me, what do you smell? And pray,

I’ll thank you, friend, for your sake, to be frank!”

Maître Renard, though high His Highness stank,

Replies: “Ah me, I’ve got a cold, I fear!

What smell?…” Wise beast! To please at court, best you

Be not too honey-tongued nor too sincere:

Answer askew, askance, as Normans do.3

>

VII, 6

THE VULTURES AND THE PIGEONS

Mars once—back when the world was young—

Caused quite a stir on high, among

The birds: great hue and cry arose

Throughout a certain race thereof.

No, not the chirping breed; not those

Spring brings to court to sing of love

In leafy bower, and rouse in us

Venus’s image amorous;

Nor those whom she—young Cupid’s mother—

Yokes to her chariot.1 Nay, another

People indeed: the vultures! They

Of piercing claw and sharp-hooked bill

Warred with each other. (People say

For some dead dog! Well anyway…)

Soon did their blood rain thick and fill

The sky! (I don’t exaggerate!)

Why, even if I attempted to,

My breath would fail should I relate

Every detail: the derring-do,

The daring feats, the battles fought,

The heroes felled, the carnage wrought…

They even say that, vulture-racked,

Bound to his rock, Prometheus2 thought

His woes were soon to end! In fact,

Long raged the slaughter. Pressed, attacked…

Bitten, clawed, hacked… Each side would use

Its strength, its valor, wile, and ruse

Against the other, doing its best

To swell the ranks of those consigned

To death’s dank shades: the dispossessed

Of life and breath… Now, while their kind

Pursue their self-annihilation,

Birds of another feathered nation,

Mottled of breast and warm of heart—

Pigeons, I mean—will do their part

To reconcile the altercation.

Envoys are sent; their mediatory

Mission succeeds: the vultures cease

Their fray, resolve to live at peace…

Ah, but that’s not quite all the story!

Soon did they turn their rage against

The ones they should have recompensed!

Pigeons, poor fools!—scores, hundreds—pay

The price, in deadly disarray,

For meddling in our cutthroats’ strife!

So? Would you live a peaceful life?

Then keep your enemies at war!

A passing thought… I’ll say no more.

VII, 7

THE COACH AND THE FLY

A coach-and-six was climbing up a hill.

Rough was the road and steep. The sweltering sun

Kept beating down upon the coach until,

At length, it stopped; and everyone—

Women, a monk, some agèd men—stepped out

To rest. The horses too, though strong and stout,

Sweating and panting, stood exhausted…

Just then a fly flew by; stopped, stared; accosted

Each of the beasts in turn. With sting and buzz

She goads them, thinks that what she does—

Sitting there on the steering-shaft

Or perching on the coachman’s nose—

Will move those wheels!… The team starts up… Ah, how she throws

Herself into the fray; goes flying fore and aft,

Here, there, up, down; plying the sergeant’s craft

At battle-stations all along the line,

Spurring her troops to victory;

And all the while complaining that it’s she

Alone who prods them on!… Our good divine,

In fact, sits reading from his breviary

(Fine time for that!). A woman sings a tune

(Or that!)… Dame Fly, our genius military,

Hums in their ears, flits, plays her tricks… Well, soon

The coach, with tireless toil, has reached the top.

“Ah,” she sighs, “finally I can stop.

It’s thanks to me they’ve reached their destination!”

And to the horses: “Now, messieurs, feel free to drop

My well-deserved remuneration.”1

Some pompous folk—this fable is about them!—

Think they’re essential everywhere:

To every action, cause, campaign, affair…

Best cast them out; we can well do without them.

VII, 8

THE MILKMAID AND THE MILK JUG

Perrette was walking, confident of stride,

Straight to the town, a milk jug on her head,

Poised on a pad along its underside.

Light was her dress and swift her tread.

That day, to be less cumbered, she

Wore but a shift and sandals flat

So that she could more agile be.

Already she was busily

Counting the sous a-plenty that

Her milk would fetch, and in her mind had spent

Them all, to buy a hundred eggs, intent

On a fine threefold brood, whereat

She mused: “No problem will it be for me

To raise a clutch of chickens in my pen.

Sly is the fox—ah, verily!—

Who, though he strike time and again,

Will not leave me enough to buy a pig,

Who will, on just a pinch of bran, grow big

And fat; bigger and fatter than when I

First bought him! And he’ll bring, I vow,

A handsome price that I can use to buy

A cow. My word, not just a cow;

Her calf as well! And both will give a leap—

Here, there—frolicking with the sheep!”

So saying, she gives a happy leap no less.

Down falls the milk: calf, cow, pig, brood, farewell!

With wistful gaze the poor proprietress

Of all that would-be wealth must now go tell

Her husband what, alas, befell;

And he, to punish and undo her,

Will doubtless put the cudgel to her.

This sorry tale a farce became

In time; “The Milk Jug” was its name.

Many will go woolgathering, fore and aft:

Castles in Spain are nothing new.

Picrochole, Pyrrhus,1 and this milkmaid too—

The great, the small, the wise, the daft—

Everyone daydreams; our illusions flatter,

Caress our sense, our soul. All wealth is ours

And ours alone. (And, for that matter,

All women too!) Boundless our powers…

When I am by myself, no man is there

So strong, courageous, that I would not dare

To challenge him; and, doughty foe,

I bring the Soufi2 down!… The folk adore me,

Bedeck my brow with diadems!… Implore me

To be their king!… Then one misstep… I go

Tumbling to earth, a-clatter. Nor

Am I more than the churl I was before.

VII, 9

THE CURÉ AND THE CORPSE

Sadly goes wending on his way

A corpse to his last resting-place.

Gladly goes wending a curé,

Eager to bury him apace.

Our dead man, carriage-borne, cadaver-wise,

Is properly and duly clapped

Into a leaden box, enwrapped

In garment fit for his demise,

And one to which one gives the name

Of “coffin”; garment quite the same

In winter chill and summer sun,

And that the dead must ever wear.

The pastor, Jean Chouart,1 drones one by one

The pages from his bréviaire:

Lessons, psalms—chapter, book, and verse.

“Monsieur, my dead friend, patience! Let

Me say them all, sure that you get

Your money’s worth, and fill my purse!”

So mused the addlepate, who eyed

His co

rpse most lovingly, lest—woe betide!—

One try to whisk him off; himself, and, worse,

The wealth he represents. His gaze

Plays on the dead man, and betrays

His thoughts: “Ah, friend! A life of ease

Shall I wrest from your obsequies:

In specie, coin, and candlewax,

And all the funeral knickknacks

That I provide.” Therewith he plans to please

Niece Paquette and her chambermaid

With racks of the best country wine

And petticoats of fine brocade…

As he will mull this elegant design,

The carriage lurches and the coffin crashes

Into our church’s luminary, smashes,

Dashes his skull to bits! And lo!

Curé and grand seigneur together go

Their way aloft!… This tale that you are reading,

About our priest who thought he would receive

Great wealth thanks to his corpse—and the preceding—

“The Milk Jug”: one may well believe

That both, unfortunately, give

A portrait of the life we live.2

VII, 10

THE MAN WHO RUNS AFTER FORTUNE AND THE MAN WHO WAITS FOR HER IN HIS BED

Who doesn’t chase Dame Fortune? Ah, how I

Wish I could choose some pleasant place to sit

And watch her flock of grovelers flit

Apace, from realm to realm, and try—

Vain band of sycophantic devotees!—

To find that wanton phantom, Destiny’s

Own daughter! Often, just as they

Approach the fickle wench, she up and flees

Their lustful grasp! Alackaday!

I pity these poor folk (for surely, one

Should have more pity for the simpleton

Than wrath!), these fools who say: “But look!

So-and-So was a cabbage planter. Now

They’ve made him pope!1 Really! And anyhow,

Where is it written in the book

That I am not as good?” “Oh, but you are!

Better, in fact, a hundred times, by far!

But what of it? Has Fortune eyes to see?

(Besides, as for the papacy, is it

Worth giving up that gift most exquisite—

The peaceful life, calm, trouble-free—

Dear to the gods themselves; gift that the Beldam

Fortune bestows upon us all too seldom!)

Don’t seek the goddess: like her sex, no doubt,

When she wants you, my friend, she’ll seek you out.”

Two friends there were—a not unwealthy pair—

Who lived together in a certain town.

One of them yearned for Fortune: up and down

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine