- Home

- Jean La Fontaine

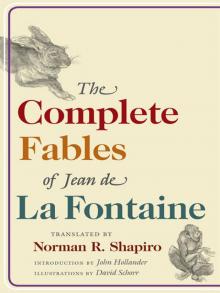

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Page 10

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Read online

Page 10

Reborn, falls to his feet. The wily beast

Catches the lazy and the slow,

And gulps each down. “What an old trick,”

He laughs. “But I have others too, for sure!

Hide though you might, your bailiwick

Will not protect you!” And again his lure

He sets: with flour spread thick about his fur,

He crouches in an open chest… Monsieur

Was right. The pitter-patter folk

Thought they might find the blasted bloke

And do him in. A rat, however—one

Well-versed in battle—knew some tricks as well;

For, having lost his tail in war’s pell-mell,

He was a veteran, second to none.

“That block, flour-sprinkled, fools me not,” he cried,

Keeping his distance from Commander Cat.

“It might well hide some war-machine inside.

Were it a sack of flour, still would I balk thereat.”

Prudent was he and open-eyed:

Mistrust, he knew, must ever be

The mother of security.

III, 18

· BOOK IV ·

THE LION IN LOVE

FOR MADEMOISELLE DE SÉVIGNÉ1

Sévigné, you whose beauteous face’s

Charm is a model for the Graces;

You who were born a beauty—whence

I ask: despite your unconcern,

Might you your generous favor turn

To Fable’s playful innocence,

And watch, though with no fear thereof,

A lion quite laid low by Love?

Love is a master curious

And passing strange; lucky are we

Who know him and his blows, rained free,

Only by what is told to us!

Thus when one speaks of him to you,

If you find truth offensive, still,

Know that the Fable means no ill.

Suffer it at your feet to do

Honor to you, rightly construed

Token of zeal and gratitude.

Back in the days when beasts could speak,

Among those who were moved to seek

Admission to our ranks, there was

The lion. Rightly so, because

Then his race equaled ours, no less,

In intellect, and comeliness,

And courage… Well, one lion of

Their number—one of high degree—

Passed by a field and, presently,

Spied a fair shepherdess. Ah love!

Smitten, he seeks her maidenhood

In marriage. Now, her father would

Surely prefer to give his child

To son-in-law a whit more mild

Of manner, and so would demur

Lest grievous harm should come to her.

But, were he to refuse, so too

Would he run a great risk to limb

And life! Or, should he hinder him

In his desire, the ingenue

Might run off one fine day and wed

Her beau in secret. Be it said—

Beside the fact that she was partial

To men of manner proud and martial—

That maids will often lose both head

And heart to lovers lush of mane.

The father, who would fain refrain

From wakening the lion’s wrath

With his refusal, treads a path

Rather more diplomatic, saying:

“My daughter, sire, is frail. And, lest

You do her injury by laying

Your paws upon her, I suggest

Your claws be clipped. As for your fangs,

They ought be filed, so that your kiss

Be best enjoyed, nor go amiss

Or harry her.” So he harangues

The beast, who, most disposed to please,

Agrees, blind to the consequences,

Like fortress stripped of its defenses.

When, then, they loose their hounds, attacking,

No means has he to send them packing.

Ah love! When we are in your thrall,

Prudence farewell, for good and all!

IV, 1

THE SHEPHERD AND THE SEA

A shepherd dwelt beside the mighty

Sea—rich domain of Amphitrite,

Wife of Poseidon—amply satisfied

To earn the pittance that his sheep were worth,

Secure, at least, despite his dearth

Of worldly wealth. But soon the tide,

Strewing the shore with treasures of the earth,

From far and wide, tempted him, and he sold

His flock: lock, stock, and barrel; put his gold

Into the merchant trade, plying the deep.

A shipwreck gobbled down his fortune. Now,

Our would-be man of means, trying somehow

To earn his bread, turned once again to sheep;

Another’s though—not like that time, long gone,

When, latterday Tircis and Corydon,

He owned the flock: now, humbly, mere Pierrot.1

In time he earned a little, bought a few

Sheep of his own: wool-laden lamb and ewe.

But when, one day, the winds, ceasing to blow

Their gales, let ships approach the shore:

“No, Water-wenches!” he exclaims. “No more!

You want my wealth? Well, fie on your design!

Try someone else, mesdames! You won’t get mine!”

This is no idle tale I tell, indeed,

Invented but to please. Experience

Proves that a single sou, when guaranteed,

Buys more than five, promised some vague time hence!

Better to be contented with our lot

And not give ear to Ocean’s tommyrot

Or vain ambition’s blandishments.

For each who tastes success, the fickle seas

Ruin ten thousand other devotees,

Condemned to wail their losses! Best beware

Lest tempests, thieves, make haste to seize their share!

IV, 2

THE FLY AND THE ANT

The fly and ant—a pair of insectkind’s

Contentious foes—were vying: each one strove

To prove the worthier. “O Jove,”

Exclaimed the first, “see how our minds

Are blinded by our vanity! That crawling

Beast dares compare herself to me!

Me, daughter of the air itself! Appalling!

My kind frequents fine palaces! Why, we

Even dine in your godly company:

For, when an ox or bull is slain, to do

You honor, I am there to taste it too,

Even before you, while my vain consoeur

Lives for three days on but a wisp of grass

That she goes dragging off to her

Dark hole!… Tell me, my precious lass,

Can you light on an emperor’s head, or on

A king’s, or on a beauteous belle’s?

Well, I can! And if I should choose, anon,

I can plant kisses on a damosel’s

Fair breast! Or frolic in her hair!

And when she would impart a brighter air

To pallid tint, she adds a beauty spot—

The one the French call “fly”1—a dot

Of blackest black… Now, after that, ma chère,

Go prattle on with all that tommyrot

About your precious larder!” “Are you through?”

Queries the thrifty ant.2 “It’s true,

Frequent fine palaces, you do. But when

You do, they curse you there! And when you

Nibble the gods’ repasts, to test their menu,

Do you improve their taste? Now and again

You squat on heads of emperors. So?

You sit on ass heads too! And woe

Attends you oftener than not t

hereby!

As for that bagatelle, that dot, that little

Beauty spot… Yes, the French do call it “fly”—

Black, love, like you (though no more so than I!)—

But how does that name give the merest tittle,

The merest jot of cause to flit and buzz

Your merits roundabout? No, coz,

Enough high-sounding talk and vile self-praise!

Flies, don’t forget, are parasites; and courts

Abound with such, all tattling false reports,

Tales, lies, till exile—or the gibbet—pays

Those fly-folk for their parasitic ways!

You and your kind will die, my dear—

Languish in hunger, misery, and cold—

When Phoebus lights the other hemisphere,

Soon, with his brilliant rays of summer gold.

Then will my labors bear their fruit. I’ll not

Go anguish over hill and plain,

Buffeted by the winds, the rain:

Sorrow and sadness will not be my lot!

My care and foresight, au contraire,

Will save me from such woe and care;

And by my deeds I’ll show you what

True merit is! But babbling here with you,

Ma chère, won’t fill my cupboards full. Adieu!

IV, 3

THE GARDENER AND HIS LORD

A certain villager—not quite

A burgher, nor a peasant—took delight

In all of gardening’s pleasures; and,

In fact, he owned a plot of land

Next to a well-kept lot, whose edge

Was bounded by a living hedge,

And in which grew, all round, thyme, salad, sorrel,

Some Spanish jasmine too… Ah, the bouquets

He made to fete young Margot’s festive days

With living tribute, vegetal and floral!

Soon, though, this pleasant state of plant affairs

Was troubled by one of your hungrier hares!

Our friend goes to the village’s seigneur,

Complains: “That damned beast comes and fills his belly—

Day, night, whenever!… Sticks? Stones? Traps? Too well he

Laughs at them all! No, he’s a sorcerer,

I tell you!” “Well, you may well think so; still

Even were he the devil, friend, my hound

Miraut will run the nasty imp to ground,

I vow!” “Oh? How? And when?” “Tomorrow will

I come.” And come he did. Next day,

True to his word, he and his men

Arrive. “Now then, my friend, what say

We eat? I trust you have a hen—

Or two, or three!—tender enough to be

A proper luncheon!… Ah! Who’s that I see,

Monsieur? Your daughter?… Come, my dear…

Come here, my sweet, and sit by me!…

Well now, is there no cavalier,

No beau who seeks the hand of this fair belle?

Methinks it’s time we find some bagatelle

Here in my purse for her!1… Dear child, come sit…”

Whence he, with lustful little pat,

Fondles a hand, an arm, lifts up a bit

Of kerchief… With respectful tit for tat

The wench resists, as would befit

A maiden… Soon her father grows suspicious;

And, as the spit turns, in the kitchen: “Oh!

What lovely hams! And fresh? They look delicious!”

“They’re yours, seigneur!” “Too kind!… I’ll take them though!…”

So goes the meal. He and his retinue—

His varlets, horses, hounds—swill down their fill,

Without so much as a merci beaucoup!

The lord, now master of the domicile,

Drinks monsieur’s wine, makes free with mademoiselle,

And does, in short, what sport he will. Lunch done,

Comes time to hunt the hare. Each one—

A horde!—prepares. Horns, trumpets sound the knell

Of his poor garden! Ravaged, overrun,

Torn up, torn down, by that marauding troop!

Farewell leeks! Farewell chicory!

Adieu forever vegetable soup!

Our hare, the while, was hunching peaceably

Under a giant cabbage… “Tally-ho!”…

He scurries through a hole. A hole? Well, no,

Rather a gaping gash, a passageway

Slashed through the hedge so that His Lordship may

Dash through on horseback! “Why such princely sport?”

Queries the gardener. Still, they smash, cavort,

And wreak more havoc in one hour than all

The hares that flourished since the days of Gaul.2

You petty princes, caught up short

In wars! Fight them yourselves! For, more you

Lose when you let the king come fight them for you!

IV, 4

THE ASS AND THE PUP

Folly it is to give the lie

To your true nature. Whence, infer:

A lout, however hard he try,

Never can be the fine monsieur.

Since but a precious few the heavens endow

With power to please, best not allow

Yourself to do what, in my tale, a poor,

Sorry ass did to court disaster.

Wanting to be more loving toward his master—

More loved as well—the silly boor,

Flinging his hooves about his neck, caressed

And kissed him, musing: “Just because

His pup’s a dear, must he alone be blessed?

What does he do? He sits up, gives his paws,

Lives with monsieur, madame… Why, him they kiss

And me they beat. Well now, if this

Is all it takes, I vow, I’ll do it.”

So, seeing his master in a festive mood,

No sooner has he mused than he hops to it,

In a most amorous attitude,

Clumsily pressing ragged horn to chin;

And, with his graceful song braying a din

To make his daring feat more charming yet!

Oh, that caress! That melody! Alarmed,

Monsieur calls for his minions, armed

With cudgels, sticks… “Help, help!…” They set

Upon the ass, whose caterwauls

Change now from song of love to wail of woe,

Beneath blow after blow… And so

The curtain falls.

IV, 5

THE WAR BETWEEN THE RATS AND THE WEASELS

Like the people known as Cat,

Weasels have no great affection

For the nation of the Rat;

And, but for the cramped confection

Of the latter’s entryways,

Many a weasel would, a-slither—

I suspect—go venturing thither,

Wreak destruction, wreck, and raze

Rat-bitats aplenty. Well

In a certain year, when flourished

Ratdom’s populace, well nourished,

Lo! their sovereign, Rat le Bel,1

Raised an army and attacked

(Though in self-defense, in fact!);

And, beneath their unfurled banner,

Weasels countered in like manner.

Each side hacked, slashed, pillaged, sacked…

If we can believe reports,

Victory long remained in doubt

As the blood of both cohorts—

Shedding, spreading roundabout—

Rendered fertile many a bare and

Fallow field. But c’est la guerre, and

One side always dies the most.

Now, the Ratovingian host

Was, alas, that side undone,

Routed by the adversary,

Crushed despite much military

Prowess shown by many a one—

A

rtarpax, Meridarpax,

Psicharpax2 by name, who, gallant,

Game, long staved off their attacks.

But in vain, for all their talent

Tactical in ways of war,

All these captains, privates, touched

By defeat—begrimed, besmutched—

Suffered Fate’s decrees. What’s more,

Though the poor paw-sloggers fled,

Safe in their retreat, quite dead,

All the royal household perished.

Why? Because each princely head

Bore some precious plume, some cherished

Gewgaw, knickknack, decoration,

Either as an honorific

Emblem, or a mark horrific

Meant to spread great consternation

Weaselwards. But only woe

Did it cause: plain folk had no

Trouble—being lithe and thin—

Slipping into crevice, crack,

Hole, or hollow; but, alack!

None was wide enough wherein

Those emplumed could safely hide:

Whence this dire rodenticide.

Thus it should be altogether

Clear that too much fuss and feather

Harms, not helps. For so much pride

Holds the great tight to their tether;

While the small, unprepossessing,

Find their modest size a blessing.

IV, 6

THE APE AND THE DOLPHIN

They tell us that the Greeks, when they

Put out to sea in bygone day,

Would bring trained dogs and apes, and thus

Make voyages less tedious;

Hence the ensuing anecdote.

Off Athens’ shores, just such a boat

Lay sinking: a catastrophe

But for the dolphins’ help; that being

Whom Pliny,1 in his History—

And Pliny knows! No disagreeing!—

Shows to have much affinity

For us and ours. Well, as I said,

Without them all the crew were dead.

Instead, they saved all they were able;

Even an ape, whose human features

Misled one of those friendly creatures.

Quite like the dolphin in the fable

(Who snatched Arion2 from the sea,

Perched on his back), our friend, about

To take the monkey shoreward, out

Of danger, asks him, casually:

“Tell me, are you from Athens, sir?”

“Surely!” our simian voyageur

Replies. “Everyone knows me there.

If you have business anywhere

In Athens, see me! I’m your man!

If I can’t help, my cousin can.

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine