- Home

- Jean La Fontaine

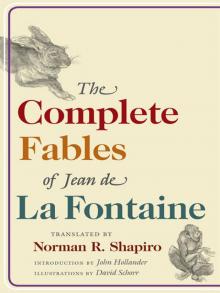

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Page 9

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine Read online

Page 9

Our death approaches—or, to be

Precise, that of our offspring. (For a mother,

Whoever says one says the other,

No?) Look below. Can you not see

How she—damned sow!—burrows and saps

Beneath the tree? It will, I fear, collapse,

And then our broods will be, most certainly,

Devoured! Ah! If, at least, merely one kitten

Be left, I should not be so anguish-smitten!”

Clambering down, she visited

The sow, heavy with young, and said:

“Dear neighbor,

Dear friend, soon will you enter labor.”

And, in a whisper, told her: “Please, beware!

You see the eagle perched up there?

Well, I assure you, if you quit this spot,

She will swoop down and leave you not

One of your litter!” And then, with an air

Of secrecy, she added: “But I pray

You take care not to say

Who told you so. For, if she knew it,

I fear that she would make me rue it!

Her wrath would fall on me!” Having thus sown

Fear here as well, and having thrown

Both families into much disarray,

The cat crawls back into her hole. The sow

And eagle are too frightened now

To forage for their young ones day by day;

The former fearing an attack, the latter—

Bird regal—worried lest the tree, a-shatter,

Fall in a heap. Rather it was their hunger

They ought have feared. It killed them all—the younger,

The older: people Porcine, Aquiline—

Profiting cats thereat in their design.

What perfidy weaves not the treacherous tongue?

Most loathed in all the universe, among

The many a woe and many a pox

And pain sprung from Pandora’s box.

Trickery and deceitfulness, I warrant,

Are much the worst and most abhorrent.

III, 6

THE DRUNKARD AND HIS WIFE

Everyone has some vice that neither shame

Nor fear can stop him from returning to.

I have a tale that shows how true

That is.1 (For never will I make a claim

That I cannot support with ample

Evidence from a good example!)

To wit: one of old Bacchus’s elect,

So much his devotee, had wrecked

His health, his mind… And even worse,

Had lost his wealth: empty of purse,

Such folk, before their race has been half-run,

Haven’t a blessèd sou. This one,

Full of the trellis-juice, one night, bereft

Of reason, thought, and consciousness, has left

His senses in the bottle. Thereupon,

His wife has him transported to a tomb

To sleep away wine’s vapors. When, anon,

He wakes, and sees the marks of doom

And death—the shroud, the candles funerary:

“What’s this?” he cries. “Is my wife now

A widow?” Whereupon said spouse, somehow

Changing her voice, masked, and in mortuary

Guise, Fury-like,2 comes to the bier, presents

A stew fit for the devil’s palate; whence

The drunkard knows that Hades now will be

His home for all eternity.

He asks: “Who are you?” “Who? Who do you think?

Hell’s scullery-nun! I bring food for the doomed

To eat, here in the nether world entombed.”

“Only to eat?” asks he. “Nothing to drink?”

III, 7

GOUT AND THE SPIDER

When Spider and the Gout were spawned by Hell,

The latter said: “My daughters, you should be

Most proud, each one, to be a fell,

Fearsome scourge of humanity,

Equally loathsome to the human race.

Now must be found the proper place

For your abodes. On the one hand,

Those hovels, huts; and, on the other, these

Fine palaces, adorned with luxuries

Abounding; gilded, great, and grand.

Such are the lodgings where you may reside.

I leave it to you to decide

Who will go where. Or, should you not,

Then let the matter be resolved by lot.”

Spider said: “Naught would make me choose to bide

In hovel vile!” Her sister, seeing

About the palaces many of those

Whom one calls “doctors,” likewise disagreeing,

Exclaimed: “For me, Gout? Goodness knows,

Those are not suited!” And she chose

The other, where she gladly settled on

A pauper’s toes, proclaiming thereupon:

“Much work shall I have, and, I guarantee it,

Hippocrates will let me be! So be it!

Here shall I stay!” Meanwhile friend Spider takes

Up residence in a rich wainscoting,

As if she has a lifelong lease, and makes

Free with her web, endeavoring

To claim the spot her own. But not

For long. For, when midges and gnats, a-wing,

Lie caught, a servant-maid sweeps up the lot.

Again the web… Again the broom… Once more

The web… And then, just as before,

Day after day… And so the poor beast went

To visit Gout. But she, more discontent

A thousandfold than the most doleful spider,

Was hard at labor. Her poor host denied her

A moment’s peace: she dug, she hacked, she hoed.

(He believed that to irk and discommode

The gout with work was a sure means to cure it!)

“Sister,” she cried, “no more can I endure it.

I pray you come take my abode,

And I, yours.” So they traded. Spider crawled

Into the hut and lived with never a broom

To fear. And Gout lodged with a prelate, whom

She soon confined, who lolled and lolled

Abed. And cataplasms? Doctors will,

God knows! not shrink from causing us more ill!

Our sisters, having had their fill thereat,

Were well-advised to change their habitat.

III, 8

THE WOLF AND THE STORK

A wolf—a glutton like his brothers:

No worse nor better than the others—

Gulped down a meal so hurriedly

He almost died. What happened was as follows:

One day, he accidentally swallows

Part of a bone. It won’t come free.

Trying to shout, he gets out not a sound,

And gestures to a stork who, coming round

Just then (as luck would have it), sets about

To probe his gullet with her beak and pull it out.

“There!” says the bird. “Now then, my pay…

Seeing I’ve saved you, sir, from choking…”

“Pay?” jeers the wolf. “You must be joking!

Some gratitude! It’s pay enough, I’d say,

That I should let you walk away

And save your neck, my cackling hen!

Now don’t you let me catch you here again!”

III, 9

THE LION BROUGHT DOWN BY MAN

A canvas at an exposition

Pictures a lion of enormous size

Felled by one man. With pride-filled eyes

The public views the fine rendition,

Until a lion, passing through,

Gives them a proper talking-to:

“It’s true, you’ve won this competition,

But only in your artist’s fantasy!

This painted victory is yo

urs;

But don’t be fooled, my friends!” he roars.

“Imagine what the scene would be

If my confreres could paint as well as he.”

III, 10

THE FOX AND THE GRAPES

Starving, a fox from Gascony… Some say

He was a Norman1… Anyway,

He spies a bunch of grapes high on a vine,

With skin the shade of deep red wine,

Ripe for the tastiest of dining,

But out of reach, hard though he perseveres.

“Bah! Fit for boors! Still green!” he sneers.

Wasn’t that better than to stand there whining?

III, 11

THE SWAN AND THE COOK

A noble’s birdhouse, once upon

A time, housed flocks of every feather,

All in a multitude together.

Among them were a gosling and a swan:

The second, meant to grace His Lordship’s gaze;

The first, to feast not eyes but palate on.

The one—one of your fancy popinjays—

Fancied himself more bosom friend than beast;

The other, at the very least,

A household pet. At any rate, our couple went,

Day in, day out, swimming about the moat,

Gliding and bobbing to their hearts’ content.

One day the cook—drunken impenitent—

Mistaking swan for goose, was going to slit his throat

And stick him in the stew, when lo!

The bird, about to die, sings out his woe.

Cook beats his breast: “Good God! You nincompoop!

A voice like that! And you were going to throw

That golden gullet in the soup!”

When dangers threaten and life’s trials alarm,

A little sweet talk does no harm.

III, 12

THE WOLF AND THE EWES

After a thousand years, and more,

The wolves decided they would end their war

Against the ewes: a wise decision

Both for the ones and for the others; for,

Although the former had a good provision

Of daily mutton (thanks to sheep that strayed

Far from the flock), the shepherds often flayed

Said beasts to make their clothes. And so each side

Could neither graze with peace of mind

Nor kill its prey. Thus is the treaty signed;

Hostages are exchanged: the wolves provide

Their cubs; the ewes, their dogs—terms constituted,

Comme il faut, by commissioners deputed

There to officiate… Well, later on,

Those little cubs grew up, until,

Like proper wolves, hungering for the kill,

And waiting for the shepherds to be gone,

They seized the fattest, juiciest lambs, and snagged them,

Strangling them in their jaws, and dragged them

Off; whilst the dogs, no longer prone to keep

A watchful eye, lay slaughtered in their sleep

(By secret agents of the wolves!), so fast,

They didn’t feel a thing: from first to last,

Each butchered by the wolves’ foul villainy.

In which we can, I venture, see

A moral: peace is good; however,

Better yet is it that we never

Disarm against a faithless enemy.

III, 13

THE LION GROWN OLD

The lion, terror of the forest, lies

Laden with years, lamenting feats of prowess past.

His loyal subjects, grown at last

More daring at his imminent demise,

Come and attack him with their newfound strength,

Each in his own most brutish wise:

Horse kicks, wolf bites, ox butts and gores… At length,

Resigned—crippled, too weak to roar—he spies

The ass approaching! O disgrace unbounded!

“I don’t mind facing death,” he sighs,

Eyeing the ass. “But you!” he cries.

“To suffer your abuse is death compounded!”

III, 14

PHILOMELA AND PROCNE

Long years ago, the swallow—she, who in

Her human form, before, had been

Procne, by name—went flying from her nest,

Far from the towns, into a wood wherein

Warbled the nightingale, and thus addressed

Her, who Philomela had been: “My dear!

Poor sister mine! How goes it? Many a year—

A thousand? More?—has passed since we

Have seen you or enjoyed your company.

Since Thrace, in fact! So? Would you languish here,

In solitude?” “What place more pleasant?”

Answers the nightingale. “What? Would you grace

Only the beasts with that uncommonplace

Music of yours? Or, at the most, some peasant?

Does wilderness deserve your gifts? Come, let them

Burst forth in cities, towns!… Besides, this wood

Recalls Tereus, your fair maidenhood,

And his foul, violent deeds! Best you forget them!”

“Quite!” says the nightingale. “And that is why

I’ll stay right where I am! For, when

Any man, now, might greet my eye,

I live through that cruel horror yet again.”1

III, 15

THE DROWNED WIFE

I’m not a man, like some, who, when they hear

“A woman’s drowning!” scoff, turn a deaf ear,

And say: “So what? What does it matter?”

I say it matters greatly. For the tender

Sex (as they’re called), the female gender,

Would be much missed. Without the latter,

Source of our joy, what would we do?

I speak of woman here neither to flatter

Nor to defend her, but, as you

Will see, because my fable tells the story,

Precisely, of a wife gone to her glory,

Alas, amid the waves. Her husband sought

To find her body, for he thought

It only proper, a posteriori,

To give it all the honors of the tomb.

Well now, it happened that some dawdlers whom

He spied, beside the stream, strolling about,

Near where she met her doom, were quite without

News of the fell event. He asked if they

Had seen madame float by. “Nay, nay,”

Was their reply. “But there’s no doubt,”

Said one, “follow the river all the way:

You’ll find her!” “Nay, not so,” another said.

“Go back upstream, back to the watershed:

A wife, despite the current’s predilection,

Surely would take the opposite direction!”

His wit was out of place, I must admit.

As for the gentle sex’s tendency

To be perverse and contradictory,

I neither can deny nor vouch for it.

Let me say merely that if she

Is born to act contrariwise,

Contrariwise a woman will

Behave throughout her days, until

Her final breath, the day she dies:

Till death… And maybe longer still!

III, 16

THE WEASEL IN THE LARDER

Weasel—that lissome-bodied demoiselle—

Risen from sickbed, though not yet quite well

(Indeed, grown wan and slightly withered),

Finding a hole of very small dimension,

Into a larder lithely slithered,

Sprightly, and with the firm intention

There to remain midst all that glut.

And so remain she did, gorging her fill,

Blithely gnawing her wanton way, until—

God knows!—no

gammon lay unscathed. Ah, but

Now what a change in her avoirdupois!

Fat, plump of cheek, bloated of gut

(All in one week!), at length she hears a noise,

Hurries back to her hole… Squeezes… “Oh oh!”

She squeals, and scurrying here, there,

Thinks that, perhaps, she errs. “No! I declare,

It’s the same hole! The one, a week ago,

I entered through!” A rat who witnessed her

Chagrin piped up: “Last week, ma soeur,

Your belly wasn’t quite so full! For, thin

You were, and sleek, when you came in;

Thin must you be when you go out.”

And we concur: there’s much to learn therein.

(But don’t infer it’s you my tale’s about!)

III, 17

THE CAT AND AN OLD RAT

I read a fabulist who told

About a second Nibblelard,1 the cats’

Own Alexander—brash and bold—

A true Attila, curse of rats,

Who made their life a hell. I read

A certain author, as I said,

Who told about this feline scourge:

A Cerberus,2 whom rats a league around

Feared unto death; a cat who sought to purge

The world of rodent creatures that abound

Here, there… Nor could those levered planks, with springs—

Those mouse-and-rat-deathdealing things

Called “traps”—hold a mere candle to

The deadly feats this cat could do.

Well, when he sees that many a rat

And mouse—like prisoners in their lair—

Do not dare leave the house, and that

He cannot find one anywhere,

The rogue pretends that he is dead,

Hanging feet first, and with his head

Hung low. (The treacherous beast held fast because

He had strings tied about his paws!)

Now then, the rodent nation looked, saw, thought

This was a chastisement for some crime wrought—

Theft of a roast, a cheese, whatever—

And that the damage done condemned our clever

Knave to this hanging, as indeed it ought!

All vowed to chortle at his obsequies!

Sniffing the air, they play at peekaboo…

Turn back… Then take another step or two…

Hesitate… Then, brave as you please,

Step out, about to seek their meal. But lo!

A different feast awaits: the dear deceased,

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine

The Complete Fables of Jean de La Fontaine